Table of Contents

- 3.1.1 – National income as a measure of economic activity

- 3.1.2 – Different Approaches to National Income Accounting

- 3.1.5 – The Business Cycle

- 3.1.6 – Alternative measures of well-being

3.1.1 – National income as a measure of economic activity

What is national income?

National income helps us understand how well a country is doing economically. It looks at all the buying and selling, making and spending that happens within a country. One way we measure this activity is by keeping track of how much stuff a country makes and sells. This is called the gross domestic product (GDP). When we talk about the GDP, there are two types: nominal GDP and real GDP.

Nominal GDP is like the total value of all the goods and services a country produces in a year not adjusted for inflation, while real GDP has been adjusted. To help us picture how money, resources, and goods move around in an economy, we use something called the circular flow of income model. This model shows how money and goods flow between households, businesses, and the government, helping us understand how everything connects in an economy.

The Model of The Circular Flow of Income

In an economy, money can come in or go out of the circular flow of income. When money is added to this flow, we call it injections, and they make the overall amount of money in the economy bigger. Examples of injections include when the government spends more money (G), when businesses invest more (I), or when there’s an increase in exports (X) – that’s when goods are sold to other countries.

On the flip side, when money is taken out of the flow, we call it leakages or withdrawals, and they make the total amount of money in the economy smaller. Examples of leakages include when households save more money (S), when the government collects more taxes (T), or when there’s an increase in imports (M) – that’s when goods are bought from other countries. It’s important to understand that there’s a lot of connection between households, businesses, the government, banks, and other countries. Everything is kind of intertwined, and changes in one area can affect the whole system.

The size of an economy is affected by how much money is added and taken out of the circular flow of income. When the amount of money added (injections) is more than what’s taken out (withdrawals), it leads to economic growth and an increase in the overall national income. But if more money is being taken out than added, it results in an economic decline and a decrease in the national income.

Any changes to things like government spending, investment, how much people buy and sell, and trade with other countries can shift the balance of money flowing in and out of the economy. For example, if interest rates go up, people tend to save more money, which means less money is being spent, leading to a decrease in consumption and investment. This, in turn, affects the overall flow of money in the economy.

The Three Ways to Calculate National Income

There are three main ways to calculate a country’s gross domestic product (GDP): the expenditure approach, the income approach, and the output approach.

- The expenditure approach adds up all the spending that happens in the economy during a year. This includes what people buy (consumption), what the government spends (government spending), what businesses invest in (investment), and the difference between what the country sells to other countries and what it buys from them (net exports).

- The income approach, on the other hand, looks at all the payments made to the factors of production in the economy. This includes wages for labor, rent for land, interest for capital, and profits for entrepreneurship.

- The output approach simply adds up the total value of all the goods and services produced within the country during the year.

Despite the different methods, they should all give the same GDP figure because one agent’s spending is another agent’s income, and the value of finished goods sold equals the expenditure paid to acquire them. It’s important to note the difference between the value and volume of GDP. The value represents the monetary worth of all goods and services produced, while the volume refers to the physical quantity produced.

How To Calculate for Nominal GDP Using The Expenditure Approach

To calculate the nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP), you add up the total spending on various components within an economy. This formula includes Consumption (C), Investment (I), Government spending (G), and the difference between Exports (X) and Imports (M), denoted as (X-M). If any of these components increase, it’s likely that the economy is experiencing growth.

Here’s what each component represents:

- Consumption refers to the total spending by households on goods and services.

- Investment represents the total spending by businesses on capital goods.

- Government spending encompasses all the expenditure made by the government, such as salaries, payments for public goods, and services.

- Net exports represent the difference between the revenue gained from selling goods and services abroad and the expenditure on goods and services from abroad. If a country exports more than it imports, it has a positive net export value, contributing positively to GDP.

It’s worth noting that if any of these components increase, it generally indicates economic growth, as more spending typically corresponds to increased economic activity.

3.1.2 – Different Approaches to National Income Accounting

In microeconomics, we delve into various markets using supply and demand analysis. We learn about the two main exchanges between firms and households: first, households spend money on goods and services, which is called consumption expenditure. Second, firms make payments to households for the factors of production they provide, such as land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship, which are known as factor payments (including rent, wages, interest, and profit).

While understanding individual markets is crucial, it’s also essential to view the economy as a whole. This broader perspective helps us comprehend how the economy grows or declines. In section 3.1.1, we used the circular flow model to illustrate factors affecting economic activity. This model shows how money, resources, and goods circulate between households, firms, and the government. Understanding this flow helps us determine national income accounting in a country.

There are three main approaches to measuring national income: the output method, the income method, and the expenditure method. Each of these methods provides insight into the economic activity within a country from different angles, helping economists and policymakers understand the overall health of the economy.

The output method

Using the method of accounting based on surveying firms’ output, it’s crucial to consider only the value added at each stage of production, rather than counting the full value repeatedly. Otherwise, it would lead to double-counting of economic output.

However, accurately measuring output becomes challenging in countries where significant informal economic activities occur. For instance, if someone cooks and sells food without formally registering their business, their economic activity remains unaccounted for in GDP statistics unless the government estimates these figures.

Despite its challenges, measuring economic data using this method provides valuable insights into the performance of different sectors within the economy. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, sectors like construction and banking were heavily affected, reflecting the origins of the crisis. Understanding how various industrial sectors fare during periods of economic growth or decline can be linked to the concept of income elasticity of demand (YED). This elasticity helps explain how demand for goods and services changes in response to shifts in income levels, shedding light on the performance of different sectors during positive and negative economic conditions.

The income method

This method of accounting involves tallying up all the income earned by different groups when they sell the factors of production in resource markets. These factors include labor, land, capital, and entrepreneurship, for which owners receive wages, rent, interest, and profits respectively.

Similar to the output method, accurately measuring national income using this approach relies on economic activity being properly recorded. However, in countries with high levels of corruption or where it’s easy to conceal economic activities, measuring GDP becomes challenging. This difficulty arises because income from illegal activities like drug trade, as well as legal but informal work such as babysitting or household care, often goes unreported and therefore remains unaccounted for.

Emerging economies often struggle with this method of accounting due to significant portions of the population lacking formal registration in government systems. This means they may not possess essential documents like birth certificates, national insurance or social security numbers, passports, or registered addresses. For instance, in India, where a substantial informal economy exists, explaining factors like the country’s highest unemployment rate since the 1970s becomes difficult. Much of the economic activity goes unreported, with the informal sector comprising almost three-quarters of the country’s jobs. Consequently, data on economic activity may go undetected, leading to misclassification of individuals engaged in periodic work as unemployed.

The expenditure method

The final method of national income accounting entails summing up the total sales receipts for all goods and services sold within the economy. In a closed economy, this primarily reflects consumption. However, in an open economy, this measure also encompasses government spending, investment, and net exports. To compile this measure, statisticians collect various transaction records, including sales receipts, credit card statements, utility bills (like electricity and mobile phone bills), and more.

In theory, the specific method chosen by a government for national income accounting doesn’t affect the final result. All three methods—output, income, and expenditure—should yield the same value for total production. This consistency ensures that regardless of the approach used, the calculated national income accurately reflects the overall economic activity within the country.

3.1.3 – Nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Nominal Gross National Income (GNI)

When governments release national income data, they typically present it as gross domestic product (GDP). GDP aims to quantify all the goods and services produced within a country during a particular timeframe. It manifests in various forms, each shedding light on different aspects of the economy under consideration. These different forms of GDP provide distinct perspectives on the economic landscape, offering insights into various facets of the country’s economic activity.

Nominal and Real GDP

When we measure output, we’re essentially tallying up the monetary value of all the goods and services produced and consumed within a country during a specific period, typically a year. However, this approach can present challenges when considering changes in prices over time.

High inflation, for example, can distort GDP growth figures, making it appear as if the country is producing more when, in reality, the increase in the sum total is largely due to rising prices rather than actual growth in production. To address this issue, economists adjust for inflation by holding prices constant, resulting in what’s known as real GDP. Real GDP provides a more accurate picture of economic growth by accounting for changes in prices over time.

On the other hand, when GDP growth is measured without adjusting for inflation, it’s referred to as nominal GDP. This approach reflects the total value of goods and services produced using current prices, without factoring in the impact of inflation.

Calculating Nominal GDP

Indeed, the circular flow of income offers a fundamental insight into GDP: regardless of whether we measure income, output, or expenditure, we should arrive at the same result. This consistency stems from the basic premise that, theoretically, all income earned within the economy is ultimately spent on goods and services. Even in an open economy with leakages, where some income may be saved or taxed, these funds are typically invested or spent by others, ensuring that the money circulates back into the economy.

Using the expenditure method

The expenditure method is employed to assess all spending within an economy. This entails measuring consumption, investment, government expenditure, and net export spending. Total expenditure is also referred to as aggregate demand (AD). This method proves valuable as it helps us understand how various segments of society, particularly households whose spending contributes significantly to GDP, react in response to economic growth, stagnation, or decline.

The expenditure method is represented by the formula:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

Here, C denotes consumption expenditure, I represents planned investment spending, G signifies government expenditure, and (X – M) indicates the trade balance, where X denotes exports expenditure and M denotes imports spending. This formula enables us to gauge the overall demand for goods and services within the economy, offering insights into its economic dynamics.

Using the output method

The output method of measuring GDP takes into account the volume of production across various industries. Economists focus on the value added to goods and services at each stage of production, rather than simply tallying the final transaction. To illustrate, let’s consider the production of a loaf of bread: from farming wheat to milling flour, baking, and finally selling it in a supermarket. At each stage of this supply chain, value is added to the product. The output method accounts for this by subtracting the value added at each intermediate step, thereby avoiding double counting.

This method allows economists to categorize production into primary, secondary, or tertiary sectors, or delve into specific industries in greater detail. Such analysis is valuable because different industries respond diversely to economic stimuli. This variation in response is often attributed to differences in the elasticity of demand, as discussed in earlier microeconomics topics. For instance, during recessions, industries may experience varying impacts based on factors such as their essentiality or the proportion of income typically spent on them. Larger purchases, for example, may be postponed during economic downturns, affecting industries differently.

Using the income method

The income method of measuring GDP focuses on the incomes derived from the factors of production, also known as factor payments. These factor payments include wages earned by labor, rent paid for the use of land, interest earned on capital, and profits generated by entrepreneurship. By tallying up these various forms of income, economists can gauge the overall economic activity within a country and assess the contributions of different factors of production to the national income.

GNI and Calculating GNI

Gross national income (GNI) is a comprehensive measure that encompasses consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports, much like GDP. However, GNI goes a step further by incorporating the incomes earned by a country’s citizens abroad and the incomes earned by foreign citizens within the country’s borders.

In essence, GNI can be summarized by the formula:

GNI = GDP + incomes flowing in from other countries – incomes flowing out to other countries

This measure is significant as it provides insights into both the domestic and international economic activity of a country. By including incomes earned abroad by its citizens and subtracting incomes earned by foreign citizens within its borders, GNI offers a more holistic view of a country’s economic performance.

Real GDP and real GNI

Real GDP and GNI can be adjusted using a deflator to account for inflation, which reduces their nominal values. In simpler terms, this process of ‘deflating’ considers how much prices have increased in a given year. Real GDP is calculated using the formula:

Real GDP = (Nominal GDP / Price deflator) × 100

Similarly, Real GNI is determined using the same formula, substituting nominal GNI for nominal GDP:

Real GNI = (Nominal GNI / Price deflator) × 100

These formulas allow economists to compare economic output and income across different time periods while accounting for changes in prices, providing a more accurate understanding of the actual growth or decline in economic activity.

Total GDP and GDP per capita

GDP per capita is a useful metric that divides the total GDP of a country by its population, giving us an average output per person. This measure offers a clearer picture of how much economic activity each individual is generating within the economy. Unlike total GDP, GDP per capita accounts for differences in population size among countries, providing a more accurate indicator of individual economic well-being. For instance, a country like Indonesia, with a large population, may have a high total GDP due to its sheer size, but its GDP per capita may be lower, indicating that, on average, individuals contribute less to the economy. This statistic allows for more meaningful comparisons between countries when assessing living standards.

Real GNI per capita is another important measure in national income accounting, revealing the income per person within the country. It is calculated by:

Real GNI per capita = Real GNI/population

This statistic provides insights into the average income level of individuals in the country, offering additional perspective on economic well-being beyond GDP per capita.

GDP/GNI by purchasing power

While GDP and GNI offer valuable insights, another method for obtaining a more accurate measure of economic size is through purchasing power parity (PPP). This indicator assesses the economy’s ability to purchase goods and services within its borders.

Purchasing power parity involves comparing prices for goods and services across different locations. In an ideal world without trade barriers or transaction costs, we might expect prices to be uniform everywhere. However, variations in purchasing power arise due to certain domestic sectors being less open to global trade, such as labor markets, real estate, or health services.

Traveling abroad often highlights these differences, as you may notice that the cost of items varies compared to your home country. The ‘Big Mac Index,’ an interactive currency tool by The Economist, serves as a vivid example. It showcases the PPP cost of a McDonald’s Big Mac hamburger in different countries, offering readers a relative benchmark for comparing purchasing power parity. By considering trade barriers and transaction costs, this index reveals disparities in the prices of standardized products, like the Big Mac, available across multiple countries.

3.1.5 – The Business Cycle

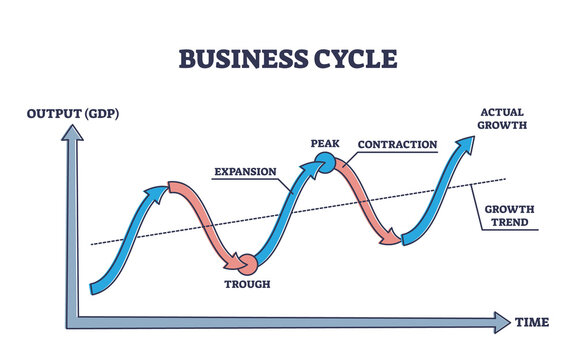

Fluctuations in economic activity over time are visualized through a diagram called the business cycle, also known as the economic or trade cycle. The business cycle typically comprises four phases:

- Expansionary Phase: This phase marks a period of increasing economic activity, characterized by rising production, employment, and consumer spending.

- Peak Phase: At the peak of the business cycle, economic activity reaches its highest point, signaling the end of the expansionary phase. This phase often coincides with high levels of employment and strong consumer confidence.

- Contractionary Phase: Following the peak, the economy enters a contractionary phase, during which economic activity begins to decline. This phase is characterized by falling production, rising unemployment, and decreased consumer spending.

- Trough: The trough represents the lowest point of the business cycle, marking the end of the contractionary phase. Economic activity is at its weakest during this phase, with low levels of production and employment.

These four phases of the business cycle illustrate the cyclical nature of the economy, with periods of expansion followed by contraction and vice versa. Understanding these fluctuations is essential for policymakers and businesses to make informed decisions and plan for future economic conditions.

Economies can begin to recover from a recession through either government intervention or natural market forces. In either case, as confidence returns and conditions improve, firms will gradually rehire unemployed workers, and demand for goods and services will increase. The specific factors that initiate this recovery process will vary depending on the nature of the recession and the underlying causes of the economic downturn.

The business cycle offers insights into the long-term growth prospects of an economy. Despite significant fluctuations, the trend line or potential output generally slopes upward, indicating the long-term trajectory of the business cycle. This line represents the economy’s long-term growth potential. It’s noteworthy that GDP can occasionally surpass or fall below this potential, resulting in either a positive or negative output gap.

However, determining potential output is challenging because it’s not directly measurable. It’s akin to estimating the potential adult height of a child – an educated guess. Additionally, defining economic recovery is complex. Is it when growth resumes, when economic potential is regained, or when GDP reaches its previous peak?

Lastly, it’s crucial to differentiate between a decrease in economic activity and a decrease in the GDP growth rate. A decrease in GDP signifies a decline in economic output, potentially leading to a recession if it persists for more than two quarters. Conversely, a decrease in the GDP growth rate indicates that GDP is increasing, but at a slower pace compared to previous quarters or years.

GDP and GNI as a measure of economic well-being

Time comparisons

To accurately compare living standards over time, it’s essential to utilize real values of GDP and GNI rather than nominal values, as nominal values can be misleading. However, even real GDP and real GNI may not fully capture changes in the population’s economic well-being. Factors such as improvements in product quality, increases in leisure activities, enhancements in education and healthcare, and other societal advancements can significantly influence people’s living standards but may not be reflected in economic measures. Therefore, while real GDP and real GNI provide a more accurate assessment, they may still underestimate or overestimate the true standard of living.

Comparisons between countries

The use of GDP and GNI for comparing economic well-being between countries has limitations. For instance, a country with a high GDP per capita may have income concentrated among a small portion of its population, while another country with a lower GDP per capita may distribute its income more evenly. However, GDP and GNI measures do not account for this distinction and can be misleading in assessing economic well-being. Additionally, other factors related to economic prosperity, such as access to healthcare, education, and social services, are not fully captured by GDP and GNI metrics. Therefore, while these measures offer insights into general activity, they may not provide a comprehensive understanding of overall well-being across different countries.

3.1.6 – Alternative measures of well-being

GDP OR GNI

While GDP is useful for measuring a country’s economic growth, it overlooks several critical factors, including the environmental impact and people’s well-being. To address this limitation, various alternative indicators have been developed. These include Gross National Happiness, the Better Life Index, the Happy Planet Index, and Green GDP. These indicators offer alternative perspectives on economic progress and can complement GDP in measuring overall societal well-being and sustainability.

World Happiness Report

In 2011, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution to include an indicator of people’s happiness in the measures of economic development. This indicator has been published each year in the World Happiness Report to give us an idea of how much happiness plays a role in human and economic development, allowing countries to address any shortfalls, if appropriate. The indicator is measured using the Cantril ladder. It is used to ask citizens of member countries to self-identify their current levels of happiness. Participants are asked to imagine a ladder where the top rung represents their happiest life and the bottom rung is their least happy. They must then measure which rung they are currently on based on that thought experiment. From this, and other measures, a general indicator can be generated.

In 2011, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution to incorporate a measure of people’s happiness into economic development assessments. This led to the annual publication of the World Happiness Report, which aims to gauge the role of happiness in human and economic development. The report allows countries to identify any shortcomings and take appropriate actions. The indicator of happiness is assessed using the Cantril ladder method. Participants in member countries are asked to self-assess their current level of happiness by imagining a ladder, where the top rung represents their happiest life and the bottom rung symbolizes their least happy state. They then indicate which rung of the ladder they currently perceive themselves to be on based on this mental exercise. Through this and other measures, a general indicator of happiness can be derived, providing valuable insights into overall well-being and quality of life.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) Better Life Index

The OECD Better Life Index (BLI) offers an alternative to GDP by measuring 11 indicators across 35 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). These indicators cover a wide range of aspects, including housing, income, jobs, community, education, environment, civic engagement, health, life satisfaction, safety, and work-life balance. The data for the BLI is primarily sourced from official sources such as the OECD, National Accounts, United Nations Statistics, and National Statistics Offices. The index relies on best practices for constructing composite indicators from a statistical standpoint.

However, the BLI has faced criticism for focusing on a relatively narrow set of indicators and overlooking others, such as community involvement and environmental degradation. Critics also argue that the criteria used in the BLI may be influenced by personal preferences, as participants can assign different weights to each factor, potentially leading to biased rankings. For instance, if comparing Canada to Belgium using the BLI, emphasizing the importance of civic engagement could result in a different ranking based on individual preferences.

Gross National Happiness (GNH)

The alternative measure of well-being developed in the 1970s in Bhutan is known as Gross National Happiness (GNH). Unlike traditional measures of economic growth, GNH takes a holistic approach to defining growth and development. It considers factors beyond purely economic aspects and emphasizes other dimensions of progress that are deemed equally important for societal well-being GNH aims to assess overall well-being by incorporating factors such as psychological well-being, environmental conservation, cultural preservation, good governance, and community vitality. By prioritizing these aspects alongside economic indicators, GNH provides a more comprehensive understanding of development and progress Since its inception, GNH has sparked widespread discussion and further economic research, prompting policymakers and researchers to explore alternative measures of progress beyond GDP. This shift towards holistic well-being measures reflects a growing recognition of the limitations of purely economic metrics and the importance of considering broader aspects of human welfare and societal flourishing.

Happy Planet Index

The Happy Planet Index (HPI) employs four key indicators to assess how efficiently residents of various countries utilize environmental resources to lead fulfilling lives. These indicators include:

- Well-being: Measures the satisfaction individuals experience with the quality of their lives.

- Life expectancy: Indicates the average lifespan individuals are expected to have.

- Inequality of outcomes: Quantifies the disparities among people within a country, expressed as a percentage.

- Ecological footprint: Represents the average environmental impact individuals exert.

Unlike other indices such as the Happiness Index and the OECD Better Life Index, the HPI utilizes a mathematical equation to calculate a country’s score on the index, rather than relying on weighted composite indicators. The equation is as follows:

Happy Planet Index (approximate) ≈ Life Expectancy × Experienced Well-being × Inequality of Outcomes / Ecological Footprint

By incorporating these indicators into a single equation, the HPI offers a comprehensive assessment of a country’s well-being while considering its environmental impact and social equality.

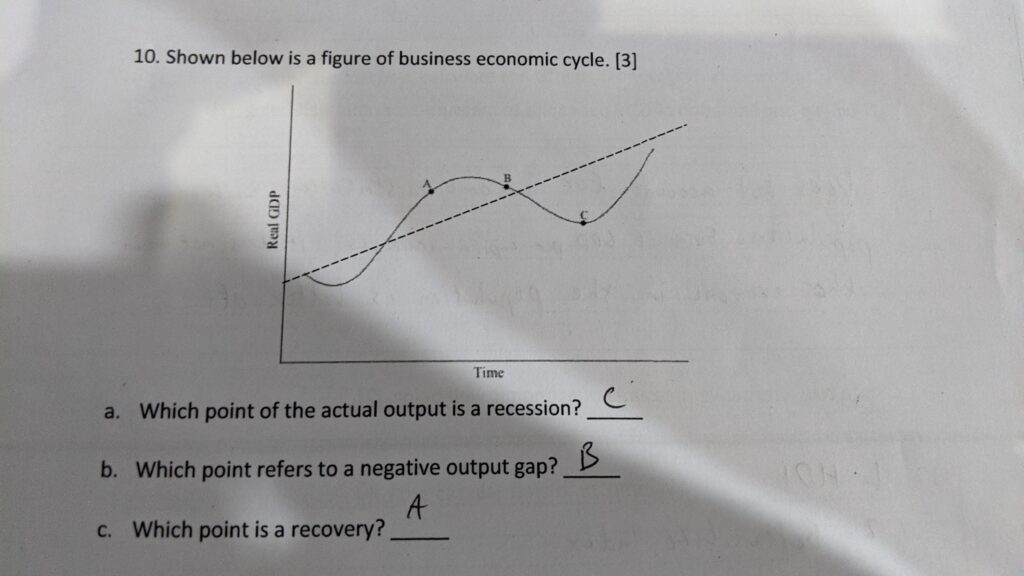

Review Questions

This is an example of a question that may appear in your exams. Quite simple, but easy to forget.

An easy way to remember:

A recession refers to the decline of economic activity over two or more consecutive quarters of a year. Although defined as a “decline of economic activity”, B is not considered a recession. Why? The real GDP gained is still net positive, therefore it cannot be immediately considered a recession. Since C is below the median line, we can safely consider the point of C as a recession. Therefore, B can be considered a negative output gap, since economic activity declines but does not result in a negative real GDP value. What does this mean? A is a recovery, as economic activity slowly increases again, thus resulting in the real GDP earned also increasing, returning to its peak.

DO NOT FORGET THE EXPENDITURE AND INCOME METHODS FORMULA OF GDP! It may actually appear as a question, and if you forget it, say goodbye to those free marks 🙁

MEMORIZE C + I + G + (X-M)

- C REFERS TO CONSUMPTION/CONSUMER SPENDING

- I REFERS TO INVESTMENTS

- G REFERS TO GOVERNMENT SPENDING/EXPENDITURE

- X REFERS TO EXPORTS

- M REFERS TO IMPORTS

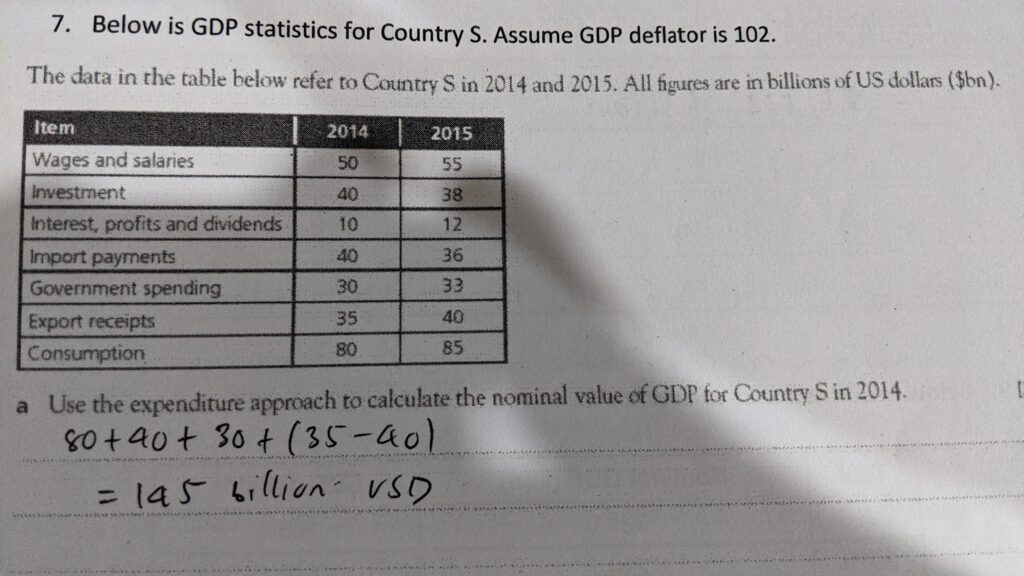

Example question to calculate for GDP:

This type of question already gives you the values of each of the components of the expenditure/income method formula, so this is essentially free marks.

Here, consumption/consumer spending is given. In 2014:

Consumer spending was 80 billion USD.

Investment was 40 billion USD.

Government spending was 30 billion USD.

Exports was 35 billion USD.

And finally, imports were 40 billion USD.

Using the formula, you would get:

80 + 40 + 30 + (35-40)

150 – 5 = 145

Thus, the nominal GDP value for Country S in 2014 is 145 billion USD.

See what I mean? All you have to do is memorize the formula, and I can guarantee you free marks for both stating the formula AND applying it to a question, but don’t take my word for it, since this is only IF these types of questions appear. If not, it’s still good to memorize the formula, because you never know.

And that’s it for Topic 3.1! See you in the next revision guide!

Psst! Check out all of our Economics revision guides here!